The story in our head directs our senses to pull out sensory data to confirm our story. We call this cognitive strategy “confirmation bias.” In a way, our whole experience and understanding of the world is based on confirmation bias.

In research methods courses we are told that we need to construct our research in such a way that we avoid confirmation bias. For example, psychology researchers are ethically required to uncover their false beliefs about marginalized people that can lead them to make perceptual errors ,that can motivate them prejudiced methods, behaviours, and outcomes, that can confirm their false beliefs. In truth, at best, we can only try to reduce our confirmation bias; we can never get rid of it and here is why…

Reality is far more complex than we can ever perceive. Wilson (2004) estimates that we are exposed to eleven million pieces of information per second. The genius—and curse—of human cognition is that we have pre-cognitive biases that help us only attend to the stimuli that are relevant (emphasis added) to our physical, psychological and social lives. (Motherwell McFarlane, 2019)

The word “story” may sound like optional, extra narratives we engage with for entertainment purposes; but make no mistake, stories can be the difference between life or death — between our survival or another’s murder. All our perceptions, learning, observations, and behaviours begin with stories directing us to only focus on what is “relevant.” and ignore the vast remainder of the “eleven million pieces of information per second” of measurable reality.

Indigenous-informed teachings begin with stories not because the stories make riveting embellishments to the subject matter — though often Indigenous stories are riveting. These wisdom stories neurophysiologically wake up and direct our brains to pay attention to what is fundamentally relevant. Indigenous stories not only tell a story but help our necessarily limited cognitive processing powers by helping us navigate through “eleven million pieces of information per second” and make sense of the world.

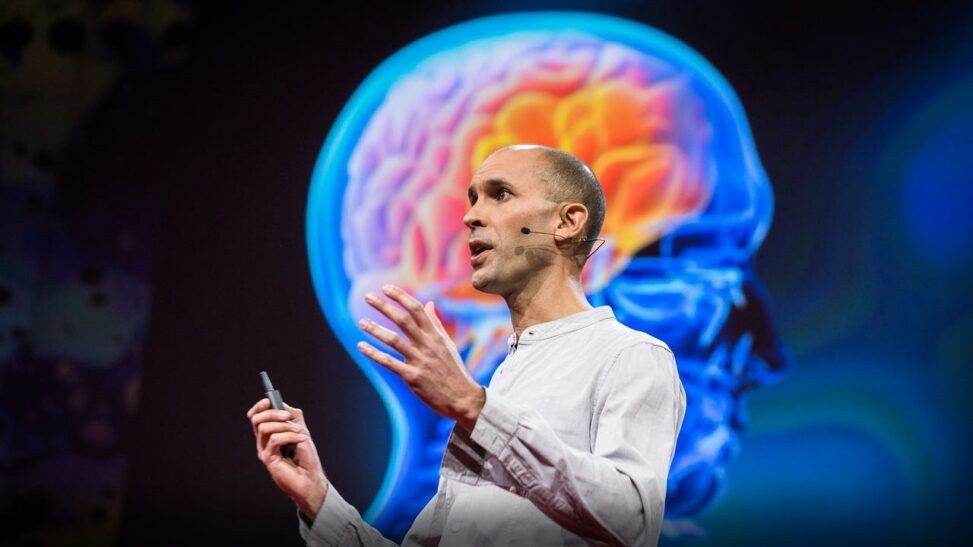

In the following TED talk, Anil Seth, provides amusing and confounding examples of the ways our brains use story — or create hallucinations — to make meaning.

Right now, billions of neurons in your brain are working together to generate a conscious experience — and not just any conscious experience, your experience of the world around you and of yourself within it. How does this happen? According to neuroscientist Anil Seth, we’re all hallucinating all the time; when we agree about our hallucinations, we call it “reality.” Join Seth for a delightfully disorienting talk that may leave you questioning the very nature of your existence.

References

McFarlane, J. M. (2019). Using Visual Narratives (Comics) to Increase Literacy and Highlight Stories of Social Justice: Awakening to Truth and Reconciliation. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 12, 46–59.

Wilson, T. (2004). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. (p. 24)